Social media products are a reaction to that which came before

As in art, so in digital communication

Welcome to 2025. As noted thinker

will tell you, if you’re over a certain age, “every year now appears absurdly futuristic.” I doubt he had a specific number for that threshold in mind, otherwise he’d just have written it out. Just the fact that I’m referencing it probably suggests my qualification though, as does my curiosity in a now 40-year-old book on communication theory: Amusing Ourselves to Death. In it, author Neil Postman basically argues that “form excludes the content” and “the medium is the metaphor,” which is to say that a method of information delivery shapes the information itself. Postman didn’t invent the idea—Marshall McLuhan coined “the medium is the message” in his 1964 book Understanding Media—but he did explore it to pretty fascinating ends at a time when TV was reshaping society’s relationship to news and politics.Ezra Klein, a political and cultural commentator whose primary form of information delivery is the same as Harris’s (a podcast), loves to reference Postman’s work in the context of America’s political landscape. This is no surprise given that we’ve just elected a former reality TV star to the office of the president for a second time and live squarely in the age of the Internet. With a variety of personalities, Klein has circled the same core point in conversation: If TV reshaped hard news and political messaging into something resembling pure entertainment, the rise of social media products in the 21st century has morphed them further into fractured sound bites, phrases, videos, and competing versions of “the truth” all depending on the nature of the platform to which they’re posted.

While it’s interesting to rabbit-hole into the concrete impact of such a dynamic through a strictly political lens, in my opinion, pretty much all you need to know is this: pre-radio presidents were best known for their written words, pre-TV presidents for their voices, pre-Internet presidents for their appearances, and social media-era presidents for their striking, embarrassing, or infuriating recorded clips. A prone-to-depression, Abraham “four score and seven years ago” Lincoln probably wouldn’t have been elected in 2024. Conversely, most people wouldn’t have known what Donald Trump sounded or even looked like had he been around to run in 1860. Much like artists, the output of politicians has long been shaped by the time in which they operated and the tools available to them. In 2025, with the tools increasingly similar for both groups, this is truer than ever.

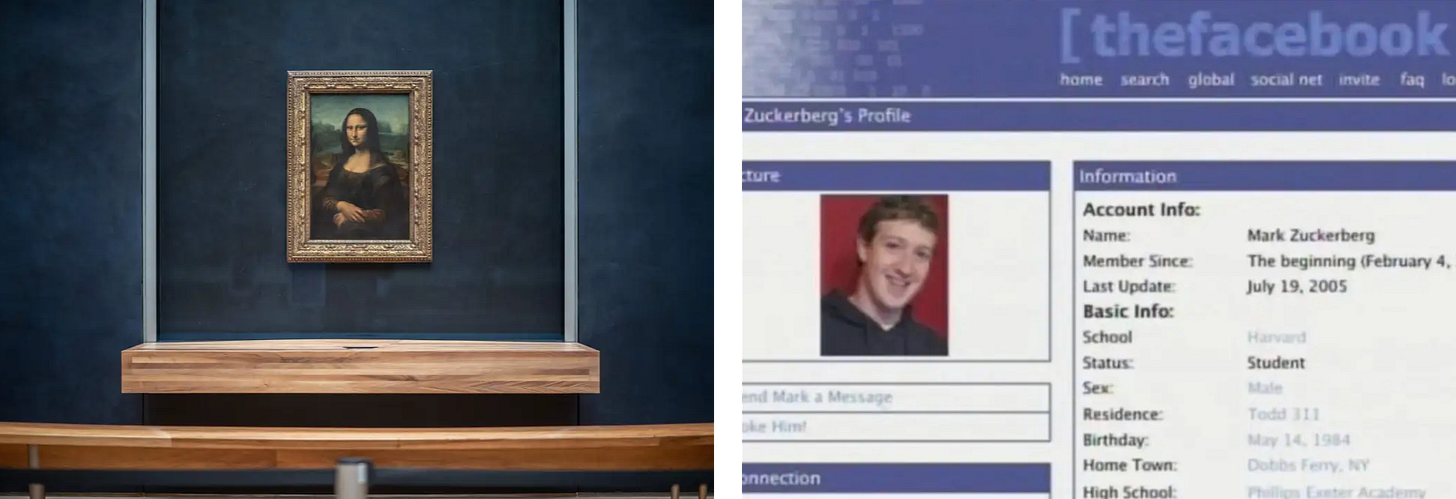

So it’s strange to consider, then, not just how much these tools shape our discourse and the vast, murky soup of politics/art/entertainment that we consume, but also how the whims of its architects dictate their state of play. After all, those architects are humans with opinions and impulses of their own. The vessels they build are just as subject to environmental influences and preceding creations as the output of an early Renaissance painter. Not to directly compare Leonardo da Vinci and Mark Zuckerberg (disclaimer: I work at Meta), but, well, the Mona Lisa (1503) was in part a reaction to the overtly religious themes of the Medieval period, and Facebook (2004) was in part a reaction to the style of directories and forums that facilitated communication through phones and the early days of the Internet. Both centered human form and expression, even if the reactions that led them there (and certainly their evolutions) were quite different.

Zoom in much closer, and you can see quite clearly on a micro level what founder reactions and their social media results have been. YouTube, beyond its Facebook-like origins as a hot-or-not service built by nerds, exploded in 2005 because its founders realized people might want an easy way to share and view public videos—like the infamous Janet Jackson wardrobe malfunction. Twitter appeared in 2006 in part based on the idea that you could share your status—a feature that existed on Facebook—directly with a small group of people. Instagram launched as something close to Foursquare in 2010 and quickly pivoted to being a photo-sharing app once it realized it was doing too much that already existed. In 2011, the founders of Snapchat looked at the pervasiveness of personal online media and launched a product that basically said: what if everything disappeared? TikTok flew onto the global scene in 2017 with fullscreen swipe-able videos that did away with the social graphs of prior products altogether.

Short-form vs. long-form, connected vs. unconnected, private vs. public, text vs. photos vs. videos. Each of these products and more have taken a look at the online social content landscape, picked an increasingly subtle lever or two to pull, and raced to market with their product. Even the slower and more intentional companies, like Substack, are an obvious reaction to that which came before—in their case, all the bells and whistle of a classic social media network, built on top of an email newsletter service powered by paid subscriptions. That’s the difference. The more the Internet matures, the more bizarre the references to previous products become. Just take a look at Mozi, an app cofounded by Twitter and Medium originator Evan Williams that promises to make “social” social again by letting you know when friends and acquaintances of yours are in town so you can see them in person. Williams decided to make this app because he was lonely after years of sacrificing his relationships for the sake of building software that in theory was meant to connect people. I’m not making fun of him. I’m just telling you what it is: solving the problem of loneliness through more software. Reacting to that which came before. Reacting to yourself.

What are the impacts of these reactions? I suppose they’re fairly innocuous if the products they give rise to don’t reach a certain critical mass. In the best case scenario, they find a sweet spot between commercial viability and small-town feel that fosters a niche, engaging community in which you can find your people—online and in real life. In the worst case, they explode in popularity and so warp the communities and content they give rise to as to force brands, politicians, and other purveyors of propaganda to get in on the fun and further deform the medium for their own specific gains. Regardless, every new product sidelines a chunk of people who are unwilling or unable to adapt to the new rules. And not just your crazy uncle, but all kinds of professionals and experts and people with specific talents to offer. It’s sort of like falling out of relevance in certain domains of public discourse beyond a certain point purely because of your age, as unfair as that can be. Except it happens not on a generational timeline, but on a timeline dictated by the breakneck pace of technological innovation.

With that in mind, look forward instead of backward, and ask yourself what comes next? What exists now on a micro scale, or has existed for a while on a macro scale, that suggests how the scaffolding for social media and online discourse might evolve? Will augmented reality glasses like Meta’s Orion produce an insane step-change in the way people interact, making possible a slew of apps and services that again reorganize the state of play and further converge entertainment, media, and politics? Will the reaction change things so rapidly that no intelligence but an artificial one can adapt fast enough anymore?

Who knows. Time will tell. The future is the message.

Great post Victor. Very insight and thought provoking. And I also don’t know what that age is but I know I am probably past it.

do you think the quality of online discourse will get better or worse in the long run? quality in terms of richness, civility, and a general sense in which social media feedback loops are positive rather than negative