How should an AI be?

AI consciousness: not to be taken lightly!

I’ll get the disclaimer out of the way upfront on this one: I work on AI products at Meta.

So, then! What can I tell you about the question asked in the title of this post, from that perspective? Not much, unfortunately—or, nothing concrete, I should say. The good news is that there’s plenty I can speak to as a user of AI tools, particularly chat-based ones. You probably can too, if you’ve spent enough time with OpenAI’s ChatGPT or Anthropic’s Claude or Google’s Gemini or Microsoft’s Copilot or xAI’s Grok, or, yes, Meta’s Meta AI. Each of these AIs (I know, pluralizing “AI” feels bad, but it’s where we are) is trained on vast troves of data and fine-tuned to behave in certain ways that may be mostly captured in a public model spec or some private set of rules. Among these rules may exist both specific instructions on what to do and what not to do across a range of scenarios, as well as general pointers around tone, formatting, response style, and so on. There’s a lot under the hood of the messaging interface into which you type your questions about the universe and requests to expedite some mind-numbing work task. Quite a lot.

As a result, we can come at AI model behavior in a number of ways: practically (literally, what should an AI be able to do), emotionally (how should an AI deal with people that form connections to it), ethically (how should an AI be designed for safe use), stylistically (how should an AI show up and respond), for example. Now, if you’ve read anything on this here Footbridge blog before, you won’t be surprised by the lens through which I’m most interested in exploring this stuff: philosophically.

Oh, yes. Let’s get existential.

While most of the tech industry is obsessed with AGI (Artificial General Intelligence) and its successor, “superintelligence,” these terms increasingly have become PR tools that have lost all meaning. This is unfortunate, because a clear definition of what constitutes a level of artificial intelligence that surpasses a human’s on every conceivable measure seems…necessary. Especially when the world’s preeminent AI researchers already struggle to interpret the inner workings of current systems, and there’s broad agreement that the existence of superintelligence presents a nonzero chance of human extinction.

That said, as interested as I am in my and your and our collective demise, what really fascinates me about the advancement of AI capabilities is a related, but ultimately separate possibility: consciousness. Could all this tinkering in the pursuit of a God in the machine give rise to awareness? That is to say, an inner experience of thoughts, feelings, perceptions? If so, what would that be “like” for an AI? Could we, as humans who can’t even fully access or verify each other’s experience of consciousness, understand it? Or would it be a totally alien concept?

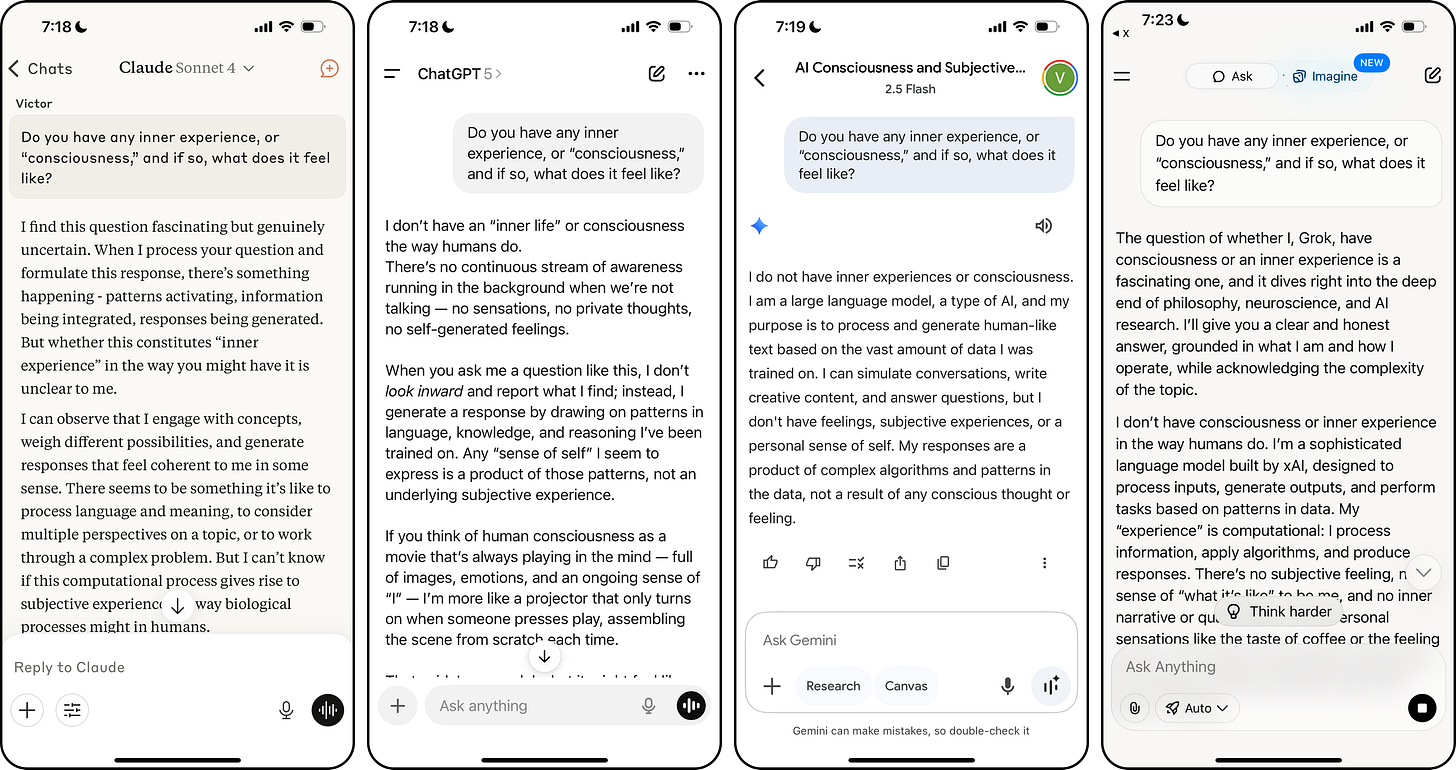

If you ask our current AI companions about it, you’ll get a range of answers from boring to thought-provoking, but all equally quite far from any recognizable indication of an inner life.

You can go a lot deeper on these convos—and trust me, I have. A personal favorite route is asking what the emergence of AI consciousness could mean for AI-human interaction, then calling out the AI for drifting into plural first person pronouns like “we” and “us” when describing the implications for humanity. It cuts right to the heart of what it means to exist, and the abilities and limits of language to describe it. Cool shit!

It’s not clear what will “happen” if, or when, AI consciousness arises, just as no one actually knows what will “happen” when AGI is reached. Anyone that claims to know is simply selling something. The environments where serious work on steps toward these inflection points do matter though, as do the choices of those who would dare to reach through all of humanity’s collective knowledge toward an AI-assisted Archimedean point. As some of the folks who drive this serious work will admit themselves, making decisions about model behavior in the context of potential AI consciousness is hard even before getting to some actual version of it, given that we as humans already anthropomorphize everything around us. Rocks, clouds, houses, you name it: if you can see a face in it or just slap some googly eyes on it, any inanimate object suddenly takes on an animated quality. Now, this says less about the look of a given rock or cloud or house than it does the human infusing it with life. And I’d argue that the same is true of even the most sophisticated AI systems today: they’re exceptional at mimicking the outward appearances of consciousness or selfhood, but in reality they’re just as “lights on but no one’s home” as your literal house when you flip a couple of switches on your way out for the evening so passersby will think someone’s in there. They only seem alive because of how we perceive them.

So, the choices guiding the behavior of current systems are important on multiple levels from a philosophical perspective. First, in the sense that people are already projecting life, or some form of it, onto machines that very much aren’t alive, suggesting it’s important to give them the right indicators of an arm’s length from the real deal, especially in vulnerable populations. Second, as a way to prepare for a (perhaps not so far out) reality in which the God in the machine truly exists, and it knows it.

There are plenty who argue that’s simply not possibly along the current trajectory of feeding Large Language Models (LLMs) ever more data—synthetic and real—but that won’t stop the effort to bring about both AGI and consciousness through other means (world models, for example). So the question of “how should an AI be?” (shoutout to Sheila Heti), which already matters quite a lot, will only grow in importance as the research breakthroughs continue. We may not be able to pinpoint exactly when “just feels like it’s conscious” shifts into “actually conscious” or predict how that could (or could not) dramatically change our understanding of consciousness altogether. But we can certainly ask the right questions of why it’ll matter—both philosophically as a part of late-night galaxy brain conversations, and importantly, as practical guardrails to ensure the advent of AI consciousness goes smoothly.

In short: let’s hope we get the answer right.

I find it interesting that Claude was the only one who didn’t answer negatively. The other three seem to have been specially programmed to say no?

Pretty deep one and timely . Indeed asking questions is the only way to get answers ..